by Jack Ringer, DDS, FAACD

It could be argued that provisional restorations don’t always get the respect they deserve from the dental community. For one thing, some dentists seem to think of provisional restorations as nothing more than an interim phase of therapy to “tide the patient over” until the final restoration is ready for delivery. For another, some dentists also are under the impression that creating highly esthetic and functional provisional restorations requires excessive chair time and material costs that would cut into their profits.

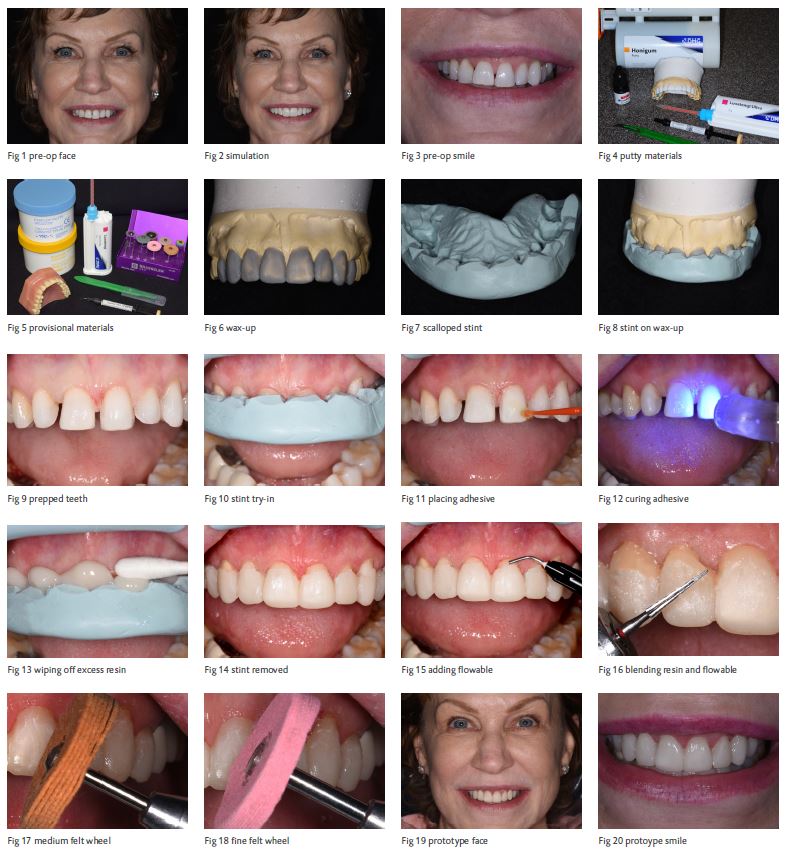

In reality, creating well designed and esthetic provisional restorations, or prototypes, can be hugely beneficial – both clinically and financially – to any practice. It’s particularly important for dentists pursuing AACD accreditation (Case Type 1) and their laboratory technician to be able to assess the potential final outcome for the proposed smile makeover in a provisional state before the final ceramics are to be manufactured. Moreover, prototype restorations also allow the patient to “preview” their smile makeover. This article will not only discuss the benefits a practice can reap from creating custom-designed anterior provisional restorations, but illustrate an efficient and inexpensive technique to perform this procedure. (Fig. 1, 2, 3)

The Prototype’s Role in the Smile Makeover Process

Creating beautiful smile makeovers has become an increasingly predictable and efficient therapy for dentists due to the evolution of newer highly esthetic and durable materials as well as adoption of tried and tested structured protocols like smile design. (Fig. 4, 5) In the past, the dentist would rely on the expertise and experience of the laboratory technician to both manufacture the restorations and determine and create the final esthetics for the case. With today’s simplified and predictable smile design procedures, the dentist can now easily take charge of the esthetic design for the case based on what’s been discussed with and decided by the patient.

A key element to designing the smile is to create a provisional restoration, or prototype, of the proposed outcome before the laboratory technician manufactures the final restorations. This phase of the smile makeover treatment is extremely valuable to the patient, dentist and laboratory technician in that it gives an accurate representation of the shape, size, position and color range that can be expected in the final restorations. Having a prototype of the desired outcome gives the patient the opportunity to assess the smile esthetics and occlusion. And if necessary, the dentist can easily make modifications since the prototype is resin-based and therefore adjustable. Once the patient has approved the overall appearance of the final prototype, the related models, photographs, measurements and any other pertinent information can be forwarded to the laboratory so the technician can manufacture the final ceramics. During the period when the patient will be wearing the approved prototype, both the patient and the dentist can feel confident and secure knowing that there won’t be any surprises when the final restoration is scheduled for delivery. (Fig. 6, 7)

Not only is this smile makeover process far more predictable and stress-free from a clinical perspective, the opportunity it provides for patients to show off their new smiles even before receiving their definitive permanent restorations is very powerful from a marketing standpoint. Photography of the prototype can also be strategically positioned alongside the final restoration in a practice’s marketing platforms to show viewers how esthetically beautiful a smile can be while going through the smile makeover process.

A Proven Technique for Smile Makeover Technique

While it might sound too good to be true, the technique discussed below truly does make it possible to create beautiful prototypes efficiently, inexpensively and predictably. But before starting the technique, it’s essential to let the patient weigh in.

After a thorough exam has been completed and any biological and esthetic deficiencies have been identified, the critical next step in creating a successful smile makeover is to “get into the head” of the patient as to what they expect for their final result. Remember, the job of the dentist is to create a design based on what the patient desires and expects. This can be achieved predictably and efficiently with patient-doctor discussions including reviewing pictures of different smiles to determine what the patient prefers. This will be followed by a thorough full-mouth exam utilizing x-rays, study models and photography to assess all the biology: occlusion, muscles, joints, and the condition of the dentition and existing restorations. This data allows the dentist to create the diagnostic design and work-up, which will include creating custom digital templates of how the teeth must be shaped and positioned, creating a 2-dimensional computer simulation, and ultimately developing a 3-dimensional wax-up. The creation of the custom prototype will then be accomplished by using the newly developed wax-up (Fig. 8,9,10) as a template while following the 5-step approach below. (Fig. 1, 2, 3)

Step 1: Assembling the armamentarium (Fig. 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 14)

The following materials are necessary to create the desired prototype:

A. Wax-up of the desired outcome

B. Putty (e.g., Exaflex, GC America; Honigum – DMG)

C. Bis-acrylic provisional material (e.g., Luxatemp Ultra – DMG; Protemp – 3M)

D. Flowable composite (e.g., LuxaFlow – DMG)

E. #12 Scalpel blade

F. Unfilled adhesive (e.g., Solo Bond – 3M; LuxaBond – DMG)

G. 12 Fluted carbide finishing bur and football carbide finishing bur

H. Felt polishing wheels (e.g., Brassler)

I. Curing light

It should be noted that no specific brands of materials are required for the effective implementation of this technique.

Step 2: Manufacturing a putty stint (Fig. 6, 7, 8)

The putty is mixed and adapted onto the wax-up, extending at least 2 teeth distal to the teeth to be prepared, as well as onto the palatal surface to ensure good stability when the stint is placed in the mouth. The stint is then scalloped gingivally using a #12 scalpel blade to expose approximately 2-3mm of tooth and papilla. Being precise in manufacturing the stint helps ensure minimal finishing and a more predictable result.

Step 3: Inserting stint with bis-acrylic material (Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13)

Following tooth preparation and acquiring all records (e.g., bite, face-bow, stump shade, etc.), the stint is tried in the mouth to confirm stability and sufficient gingival tooth and papilla exposure. The prepared non-etched teeth are then to be coated with a thin layer of an unfilled resin, air-dried and light-cured. This step aids in retaining the resin and reduces the chance of gingival brown line stain by creating a better seal. The bis-acrylic material is then injected into the stint and inserted in the mouth. Before the material sets, all excess material is wiped off, exposing the gingival 2-3mmm of tooth structure. Note that as the stint is not bonded to the prepared teeth, removal at the seating appointment can be achieved without using a rotary instrument on tooth structure; which potentially could damage the preparation. However, before trying in and bonding the definitive restorations, the prepared teeth need to be air-abraded or pumiced to ensure that

any residual resin is removed. (Fig. 15)

Step 4: Customizing the esthetics of the prototype (Fig. 14, 15)

After the bis-acrylic has set up, the stint is removed to reveal the completed shape of the prototype with the exception of the prepped teeth apical to the tip of the inter-proximal papilla. The final shape of the prototype is completed by directly applying to the exposed tooth structure a flowable resin whose color is a lower value than that chosen for the prototype. The flowable resin is then cured. By incorporating this step, a polychromatic appearance for the prototype can be achieved as well as creating a better seal at the gingival margin, which aids in retention. (Fig. 16, 17, 18)

Step 5: Finishing and polishing the prototype (Fig. 16, 17, 18, 19, 20)

The final step is to blend and finish the bis-acrylic and flowable composite utilizing fluted carbine finishing burs as well as medium and fine felt wheels. Since the initial application of the bis-acrylic and the application of the flowable resin did not impinge or violate the gingival tissues, finishing and polishing the bis-acrylic and flowable resin can also be completed without damaging the soft tissue. After checking occlusion, making any necessary adjustments and taking photographs, an impression of the final prototype is taken and forwarded to the laboratory technician. The patient is dismissed and advised that after “wearing” the prototypes for a few days, they must return if they feel any esthetic modifications are needed. Any modifications are then relayed to the technician before the final restorations are manufactured.

Conclusion

Creating an accurate “preview” of what the patient desires is critical to the ability of the dentist and laboratory technician to achieve a beautiful smile makeover outcome. If the “preview” can be accomplished in an efficient and predictable manner, it makes the smile makeover therapy more seamless, less likely to require the remaking of restorations, and therefore less expensive. Importantly, it will also make the process more convenient and satisfying for the patient. As a bonus, it will enhance the optics and marketing of the practice. (Fig. 19, 20)