Written by Dr Jack Ringer, DDS, FAACD, FIADFE

Dentists routinely face the challenging clinical situation where the coronal portion of the tooth is so significantly deficient that it will not allow sufficient retention for the definitive restoration. To overcome this problem, the coronal portion of the tooth needs to be augmented by “coring” up the tooth which will allow for appropriate retention of the restoration. Building up a core for a tooth is very predictable using today’s modern materials and bonding protocols as long as there is sufficient tooth structure for the core material to adhere. In many cases where there is extensive coronal deficiency either due to trauma or disease, the tooth may need or was previously treated endodontically. Therefore, in these circumstances, a post is placed in the root canal space from which the core material can attach as well as to any remaining coronal tooth structure. Combining adherence of the core to the post and the remaining coronal portion of the tooth will provide a predictable outcome for the post/core complex. It must be stated clearly, however, that at least a 2mm circumferential ferule of healthy tooth structure must exist as well since a post and core alone are not designed to be the sole factor for the retention of the definitive restoration! If an inadequate ferule exists, a crown lengthening procedure or extrusion of the tooth must be employed before creating the final tooth preparation.

One must understand the types and properties of the various core and post materials that are available in order to choose what is appropriate for any particular clinical situation.

Posts

Posts have been available to dentists for many decades and have been manufactured in various materials such as metal, gold, fiber reinforced resin, ceramic, and zirconia. Post/core complexes can also be laboratory manufactured as one piece. Each have their pluses and negatives, such as cost, efficiency and predictability, but the general consensus today is that the dentist’s wish list

for a post is to have the following characteristics:

- The post to be pre manufactured in various sizes and not have to be lab manufactured

- The post to have some degree of flex so the post will not exert force on the tooth that could precipitate a root fracture

- The post placement technique to be predictable and efficient

- The post to have some degree of radiopacity

- The post to be bondable to the tooth structure as well as the core material

Core Material

Over many decades core materials have been made of various materials such as gold, amalgam, composite and other glass reinforced resin-based materials. Each have their pluses and negatives, but the general consensus today is that the dentist’s wish list for a core material is to have the following characteristics:

- The core material to be radiopaque

- The core material to be easily sculpted without excessive slumping

- The core material to be easily dispensed using syringes or gun cartridges

- The core material to cut similarly like dentin

- The core material to have a dentin appearance

- The core material to be bondable to tooth structure and ceramic or resin-based posts

- The core material to be dual cured

- The core material to have significant tensile strength, i.e., zirconia fillers

Techniques

There are 2 accepted and predictable techniques for placing a post and core, providing the operator is utilizing today’s modern materials.

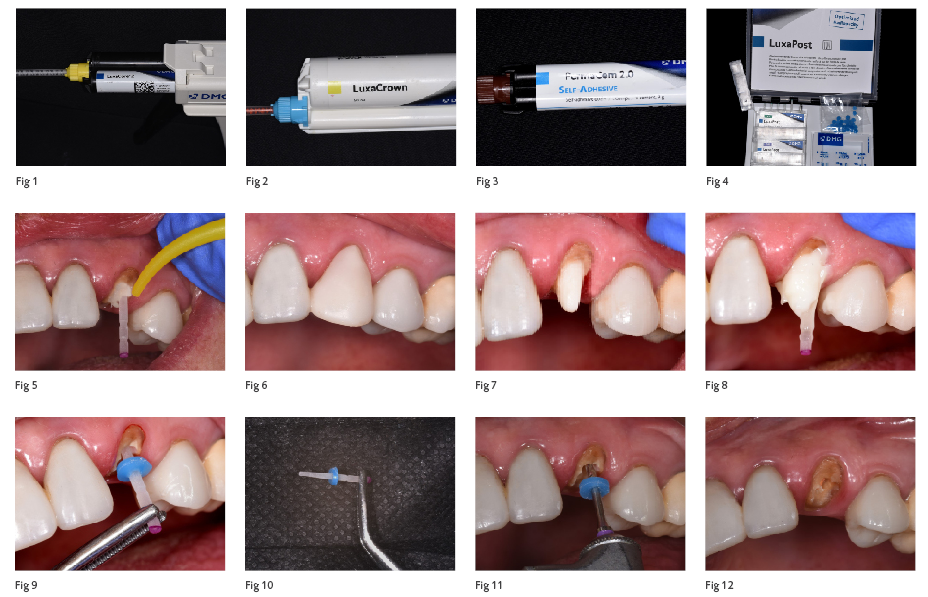

The first is where the canal is prepared for the acceptance of the post, followed by bonding the appropriate fiber reinforced post (Fig. 1, e.g., LuxaPost -DMG) into the canal with a dual cure resin adhesive and resin cement (Fig. 2, e.g., PermaCem 2.0 – DMG), and finally applying and sculpting the core material (Fig. 3, e.g., LuxaCore Z Dual – DMG) onto the post and the coronal portion of the tooth. The final preparation is completed by shaping the core to the desired shape as well as placing the definitive margin on the coronal portion of the tooth utilizing a diamond bur on a rotary instrument.

The second technique is the same as the first technique, except the post is bonded in the root canal space with a resin adhesive but utilizing the core material as the resin cement. The first step for this technique is to treat the canal and tooth with adhesive. The next step is where the core material is injected into the canal and onto the post, followed by seating the post and adding the necessary additional core material to create the definitive core. This technique is known as the “mono block” technique. In order for this technique to be predictable and successful, the core material needs to be dual cure as well as having a delivery system whereby the core material can be flowed into the canal.

There are several products available on the market that can be used for either of these techniques. However, this author finds that the DMG product line, previously described, satisfies the ideal wish list for creating a chairside efficient and predictable post/core complex.

The following describes and illustrates treating an endodontically treated tooth with a post and core build up, followed by placement of the definitive restoration utilizing the “mono block” technique.

The patient presented with an endodontically treated maxillary left cuspid (#11) fractured off at the gingival margin (Fig. 4). Diagnosis revealed that restoring the tooth would be predictable as

the root was healthy, periodontally sound and had sufficient length. However, due to the position of the most coronal portion of the tooth in relation to the gingival margin, a crown lengthening procedure or root extrusion would be required to create an adequate ferule. Those options were discussed with the patient and due to the fact that a minimal crown lengthening procedure would be all that was needed, the patient opted for crown lengthening versus orthodontic extrusion. It must also be noted that though the definitive gingival margin would be a bit more apical after the procedure, the esthetics would not be impacted as gingival asymmetry would be negligible, plus the patient does not display the gingival margin when smiling due to a low lip line.

Since the final restoration could not be completed until the crown lengthening procedure was completed and matured, the patient would have to be in a prototype restoration for several weeks. Fortunately, the patient was able to bring in the fractured coronal portion of the tooth at this emergency visit, making it predictable to secure the piece in place in order to take an impression and pour a model in order to create a stint to develop the definitive prototype restoration.

The decision at this appointment was to permanently place the definitive post (Fig. 5, e.g., LuxaPost – DMG) and core utilizing the “mono block” technique. The canal was prepared with a slow speed handpiece with the appropriately sized file (Fig. 6). This was followed by confirming the fit of corresponding post in the canal (Fig. 7). The post was then bonded into the canal by first scrubbing a dual cure resin adhesive into the canal and then coating the post with the same resin.

The post was then coated with the core material and inserted into the canal (Fig. 8) after the same core material (LuxaCore Z Dual – DMG) was flowed into the canal; and this was followed by light curing (Fig. 9). It must be noted that even though dual cure adhesives and resins achieve adequate bond strengths without light curing; micro hardness at the surface is increased, working time is shortened as well as achieving an initial higher bonding conversion rate with the application of light curing.

The post and core complex were then definitively prepped along with a minimal preparation of the existing coronal portion of the tooth (Fig. 10). A custom prototype restoration was manufactured chairside utilizing the stint designed from her original tooth shape. The material chosen for the prototype would be a long lasting bis-acrylic material (Fig. 11, e.g., LuxaCrown – DMG) as the patient would need to be in the prototype for approximately 2 months as the periodontal tissues mature. The final prototype was finished and polished followed by luting with a provisional resin cement (Fig. 12).

At this point, the patient was provided with a referral to the periodontist for the crown lengthening procedure. Once the tissue has matured for several weeks, the patient will return for final tooth preparation, fabrication of the definitive restoration followed by permanent cementation.

Utilizing this efficient technique and the materials described, the operator and patient can have great confidence that the final prothesis will be predictably sound; biologically, esthetically and functionally; assuming there is adequate hygiene and the absence of excessive trauma to the tooth.